ggirtsou's Blog

Thoughts on software and architecture. GitHub

Exchanging messages in microservices

Photo by Startaê Team on Unsplash

In this post, I am going to cover what microservice messages are and why we need them, troubleshooting steps, and suggest a visualization tool to track their flow.

Why do we need messages?

In the microservices world, we need to pass information about events that occurred from one service to another. This works well for asynchronous communication. If you want to block and wait until you get a response make a synchronous call via REST or RPC.

What is a microservice message?

A message represents an event that occurred and matters for your applications. You send it to inform another service that an event took place, and the receiver (also known as a consumer) will take appropriate action on it.

Messages can be in different formats, JSON and binary data being the most common. You should use whatever format makes sense for your use case — some tools to check out: Protobuf, gRPC Avro, Thrift, and Cap’n Proto.

What is a microservice pipeline?

You might have heard the term pipeline. This can be used in different contexts, for example, a CI or a data pipeline. In the microservices world, it refers to the various services working together towards a common goal.

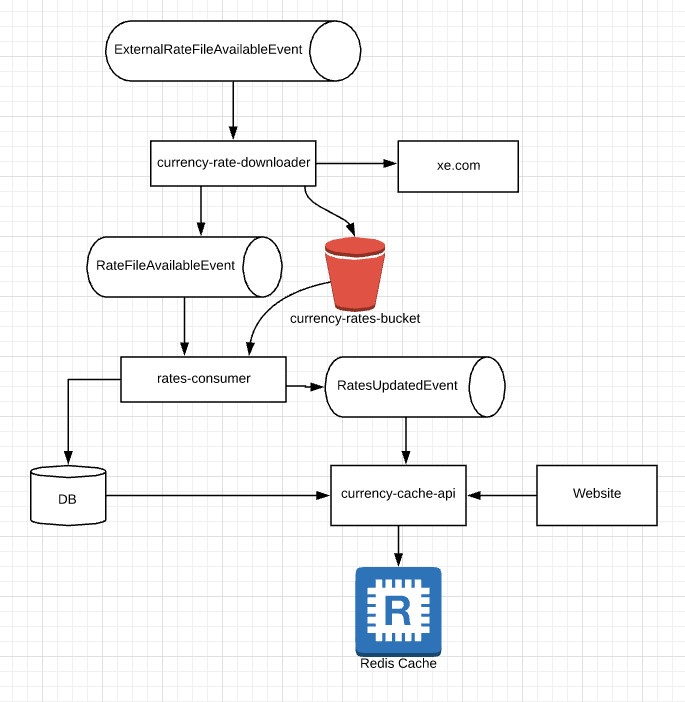

Consider this example:

Microservice 1receives a message that a file with new currency rates is available, so it downloads it from a remote host and uploads it to AWS S3. It creates a message that currency rates file has been uploaded in S3 containing its location.Microservice 2downloads that file and updates theratesdatabase and creates a message.Microservice 3clears the rates cache and warms up the cache. Now the website can serve up to date rates to the client.

Although small, the above is a microservices pipeline.

How are the messages transmitted?

Glad you asked! Through the PubSub pattern. There are many open-source tools, such as Apache Kafka, NATS, or managed like Confluent, and AWS SQS. The terminology varies slightly in each tool, but the concept remains the same:

- You have topics that hold the messages

- Services create and consume messages from topics

On the tech side of things, there’s a lot more to it, such as node coordination since it operates as a cluster, partitioning, order guarantees, and last but not least gracefully handling failures and recovering.

How do I know where a message failed?

As with everything, distributed systems come with tradeoffs. Services can fail at any point, an upstream dependency might be down, or a message could contain data that cause our services to crash.

So we need visibility in the pipeline. The first step of achieving that is by using correlation IDs. The way this works is, every time you get a new message at the beginning of your pipeline, you generate and assign it a UUID. When that message is handled by the next service and another message is generated, use the same correlation ID to track its flow in the pipeline.

What happens with failed / invalid messages?

You have to think about how you want to handle it. If you don’t handle failures, the queue will be blocked if your consumer processes one message at a time. Letting your consumer get stuck might be desirable if you don’t have a process established on how to handle failures.

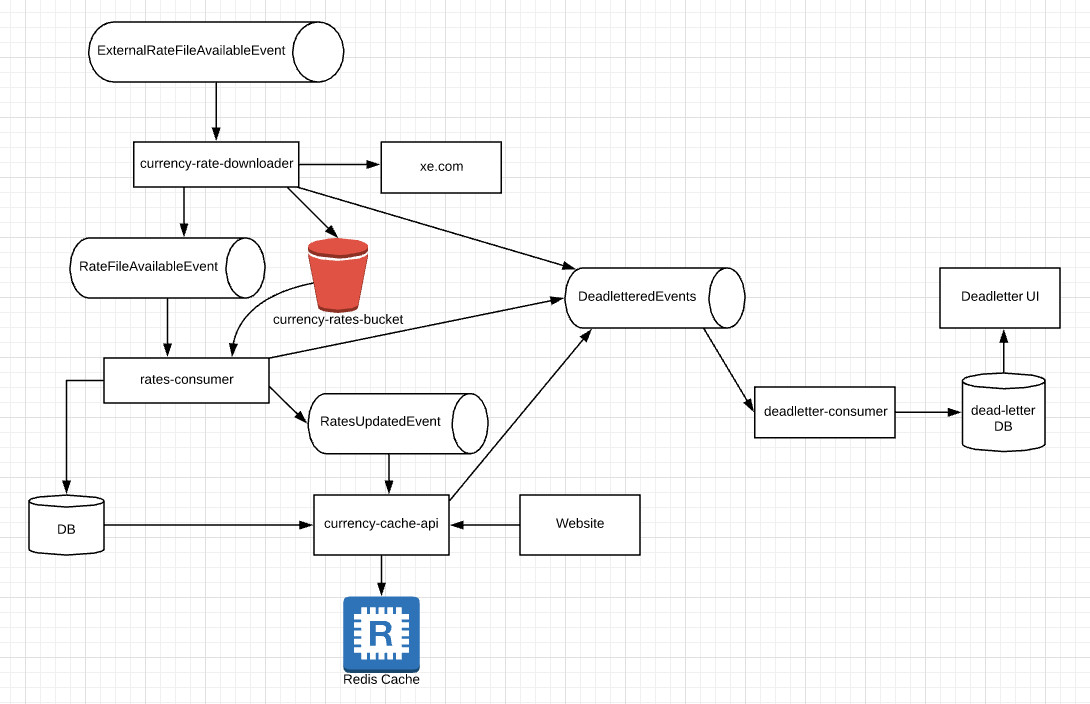

If you want to continue processing messages even when one fails, you can send the failed ones to another queue called “dead-letter queue”. That’s a special queue where all the bad messages are redirected.

Pro Tip: Have metrics consumed_messages and failed_messages and increase them when appropriate so you can tell from a dashboard what’s happening in your consumers (without having to check the logs for errors).

Pro Tip 2: Have a retry mechanism with exponential backoff for API calls, as you can avoid dead-lettering a message for temporary network failures.

With that system in place, you can create two useful alerts:

- Trigger an alert if no messages were processed in the last

Nhours - Trigger an alert when a consumer has >=20% error rate for the last 30 mins.

What happens in the dead-letter queue?

This is where most people cut corners. They know dead-lettered messages are important for the business and need to be investigated, but it requires human input. Defining processes and learning what the errors mean takes time. Humans want to do fun things and looking at exceptions is not necessarily exciting.

Keep in mind, systems generate a lot of messages, and you don’t want to be in a situation where systems are blocked with thousands of messages because you didn’t set it up properly.

What you can do, is to expose the dead-lettered messages in a UI for a group that knows how to fix them (business analysts, or developers for code exceptions). This design takes time and effort to get there because you need to:

- store or index the messages,

- present them in a UI with pagination, search, and filter functionality

- have a re-submission mechanism that will send it to the original pub/sub topic and set a new correlation ID

Surely you understand why people want to cut corners and skip this because they have to do it for every pipeline that uses pub/sub. Or you can be smart about it and try to make it more generic and configurable to allow handling failed messages from different pipelines in the same system.

Alternatively, if you don’t want to make a UI to resolve exceptions, you can send automated notifications to a group that’s interested in those failures.

Can I delete a message that’s blocking my queue?

No. I know, it is painful, but you have to send it to a dead-letter queue, investigate why it failed and resolve it. In event sourcing, a message should never be deleted. You can create a new one that offsets it, but you should not delete it. Even if your databases get destroyed, the state of your systems should be the same if you replay the messages from the beginning of the topic.

Consider this example: a customer’s balance is set to the wrong amount by a bug. To fix it, you don’t delete the message or update the database directly, but create a new event that sets it to the correct amount.

Visualizing message flow - a.k.a troubleshooting in a pretty way

Consider this example: your pipeline activates customer devices upon customer payment. It has 12 microservices, and your analyst asks you “can you find out why a device with ID xyz was not activated?” If you don’t log the deviceID in your error logs (or don’t have a centralized log aggregation system), then you have no way of finding an answer to this.

What if you had a system that even your analysts could use and find out on their own?

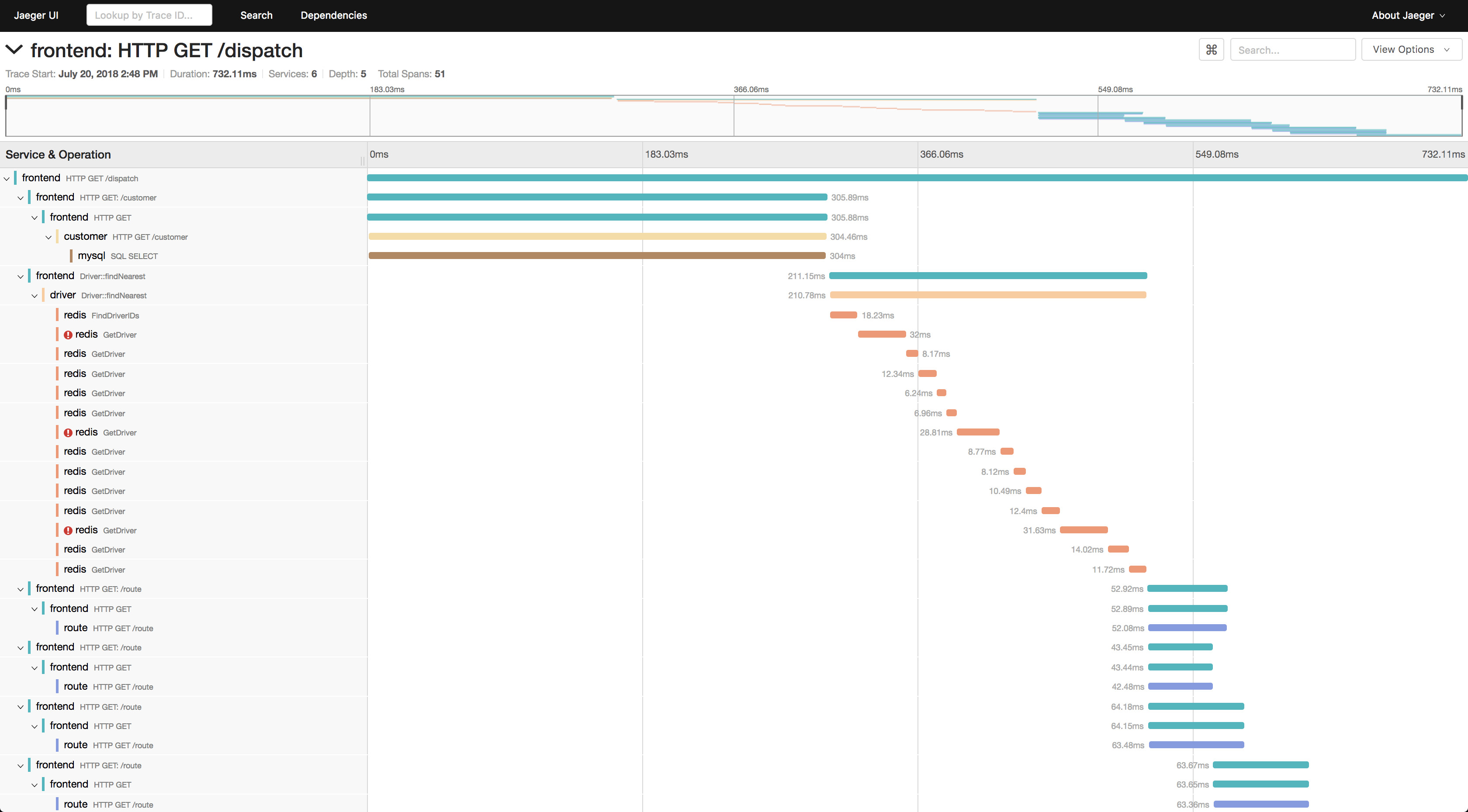

Meet OpenTracing and Jaeger. Both open-source products allow you to create traces from your microservices with metadata. Make sure to pay attention to sample rate if you’re interested in storing all traces.

Useful metadata for the above pipeline would be correlation ID and device ID. If you always have a correlation ID and use that in traces, then the UI will let you search by that tag and then shows you the journey your message took. You can even view the error in the UI if you want to, and see precisely at what step it failed.

No need to spend hours checking the logs, or getting interrupted from your work to troubleshoot mysteries. If its a code error, you have the answer in minutes and you can focus on the fix rather than finding an answer.

Be aware it takes a long time to adapt it to existing systems, as you have to think about what’s useful to you, and how you are going to do your searches. Also, don’t forget the code changes! Besides that, your team has to learn how to operate it and have a disaster recovery plan.

Prepare a presentation for your team and talk about the benefits to senior stakeholders to make sure everyone is on board with this decision, as it will require development effort. Remember, sometimes we have to go slow to go faster later!

Your experience

I’d love to hear your thoughts about microservices and problems you encountered. Feel free to reach out to me on LinkedIn!

tags: microservices - event - sourcing - deadletter - contracts - pipeline